This is the sermon I preached this morning at Barnes Methodist Church. The texts for today were 2 Kings 5:1-14 and Mark 1:40-45. Both passages refer to the healing of lepers. In the book of Kings, we meet a powerful general called Namaan, who crosses from Aram (very roughly, modern-day Syria) to Israel for a cure. In the New Testament passage, Jesus heals a leper at Capernaum, a town on the shores of the Sea of Galilee where we believe Jesus lived for some time.

“Are not … the rivers of Damascus better than all the waters of Israel? Could I not wash in them and be cleaned?” (1 Kings 5:12) Naaman wished to be healed; but he did not wish to be healed like this. Given the context, his reluctance and anger were perhaps understandable. He was a very important man, a great warrior and a favourite of the king. He had come from a more important and more powerful nation than Israel. He had come bearing gifts with a grand retinue, and no doubt cut an imposing figure. And here he was in this one horse town, and not only could the local prophet not even be bothered to see him but the remedy he was proposing seemed utterly contemptuous.

“Are not … the rivers of Damascus better than all the waters of Israel? Could I not wash in them and be cleaned?” (1 Kings 5:12) Naaman wished to be healed; but he did not wish to be healed like this. Given the context, his reluctance and anger were perhaps understandable. He was a very important man, a great warrior and a favourite of the king. He had come from a more important and more powerful nation than Israel. He had come bearing gifts with a grand retinue, and no doubt cut an imposing figure. And here he was in this one horse town, and not only could the local prophet not even be bothered to see him but the remedy he was proposing seemed utterly contemptuous.

It is perhaps too easy, though, to contrast the general’s pride and seeming reluctance with the ready faith of the leper whom Jesus encountered at Capernaum. In truth, Naaman too had been incredibly brave in seeking out the prophet Elisha. You will recall that the original suggestion for his visit had come from his servant – and not only a servant, but a young girl and a foreigner. He then had to undertake an arduous and lengthy journey to find this Samaritan prophet. And ultimately, with a little cajoling from his servants, he did do what he was told and bathed seven times in this second-rate foreign river, and was indeed cured.

Perhaps, instead of contrasting the stories, we should seek the similarities and note that in both cases desperation drove these two men to find a cure for their illness. A cure that for neither of them was easy nor cheap.

The leprosy we frequently encounter in the Bible is not quite the same as the modern disease, usually referred to as Hansen’s Disease, which agencies such as the Leprosy Mission do so much to combat. The Biblical condition seems to have included a wide range of skin conditions, including psoriasis, lupus and ringworn, that could involve discoloration or flaking of the skin. It was not as contagious as is often believed and could indeed be cured in some cases. However, whatever the name, the effect of both the modern and ancient diseases was the same: social exclusion and rejection of the sufferers.

The leprosy we frequently encounter in the Bible is not quite the same as the modern disease, usually referred to as Hansen’s Disease, which agencies such as the Leprosy Mission do so much to combat. The Biblical condition seems to have included a wide range of skin conditions, including psoriasis, lupus and ringworn, that could involve discoloration or flaking of the skin. It was not as contagious as is often believed and could indeed be cured in some cases. However, whatever the name, the effect of both the modern and ancient diseases was the same: social exclusion and rejection of the sufferers.

The Levitical Law – the law laid down in the book of Leviticus – was clear: the disease made a person unclean and that they had to live apart from the rest of the community. This may explain why Elisha was unwilling to meet Naaman, in fact. It was the priest’s role to assess the nature of the afflicted person’s condition and undertake the necessary rituals and sacrifice once the illness had cleared up. This is what Jesus refers to when he tells the leper to show himself to a priest and offer what Moses had commanded. Only in this way could the leper re-join his society.

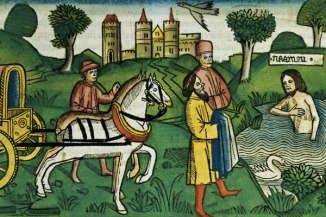

A medieval leper bell

Leviticus 13 makes clear, though, that the sufferer could not hide their condition or their shame, if the disease persisted:

The person who has the leprous disease shall wear torn clothes and let the hair of his head be dishevelled; and he shall cover his upper lip and cry out, ‘Unclean, unclean.’ (Leviticus 13:45)

Even for the mighty general Naaman, who was not a Jew, leprosy meant not being a whole person. The first few verses of our OT reading tell us that clearly: he was a great man, he was in high favour with the king, he had achieved a great victory … but he was a leper. In other words, it didn’t matter what else he did or achieved, it was his leprosy by which everyone ultimately judged him. The comparisons to modern sexism, racism or homophobia are easy to make. “She’s an excellent brain surgeon … for a woman.”

If this were true for the rich and powerful Naaman, how much more so then for the poor leper who approached Christ. We are told almost uniquely in Mark that Jesus looked on the man “with pity” or “compassion” – something that we are not otherwise told about Jesus’s other acts of healing. Perhaps this was thought noteworthy because so few people had ever looked on this man with ‘pity’ before – revulsion and fear, possibly – but not pity.

Like Naaman, he was in fact desperate and had nowhere else to turn. And this desperation drove both men to seek a cure, however costly or risky that might be. And we encounter many such people in the gospels. In Mark alone, we could think perhaps of Jairus, the respectable local synagogue leader, whose daughter was dying and who literally flung himself at the feet of Jesus, the wandering healer, in desperation. Or perhaps, the woman who had been subject to internal bleeding for 12 years, something which again made her ritually unclean. She knew that just by touching Jesus – or any other member of the crowd that pressed around him – she would make them unclean too, and risk their wrath. But she reached out for the hem of his garment regardless – in desperation. And we could name others.

Like Naaman, he was in fact desperate and had nowhere else to turn. And this desperation drove both men to seek a cure, however costly or risky that might be. And we encounter many such people in the gospels. In Mark alone, we could think perhaps of Jairus, the respectable local synagogue leader, whose daughter was dying and who literally flung himself at the feet of Jesus, the wandering healer, in desperation. Or perhaps, the woman who had been subject to internal bleeding for 12 years, something which again made her ritually unclean. She knew that just by touching Jesus – or any other member of the crowd that pressed around him – she would make them unclean too, and risk their wrath. But she reached out for the hem of his garment regardless – in desperation. And we could name others.

In contrast, though, we could think of the story that we read later in Mark, of the Rich Young Man. He too comes to Christ. He too, we are told, kneels before him. He too has a demand to make on Jesus: “Good teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?”. Is this a cry for healing too? A desire to be made whole? A recognition that, though like Naaman he has wealth and power, there is something missing in his life?

Jesus does provide a remedy for the young man; one as shocking as Elisha’s response to the visiting general – “go, sell what you own and give the money to the poor”. But, unlike Naaman, the rich young man refuses to take the medicine prescribed. It is too bitter a pill to swallow. The cure seems worse than the disease.

To how many situations and challenges in our world and in our lives could we apply that lesson, I wonder? As I reflected on the readings this week, and the story of a powerful general from Damascus, perhaps inevitably my mind turned to what is currently happening in Syria. To the terrible destruction of that ancient country, the bitter and brutal civil war, and the millions who seemed destined to spend the rest of their lives in refugee camps. There are things we as an international community could have done, and could do still, to help the people of Syria but the cost seems too high.

To how many situations and challenges in our world and in our lives could we apply that lesson, I wonder? As I reflected on the readings this week, and the story of a powerful general from Damascus, perhaps inevitably my mind turned to what is currently happening in Syria. To the terrible destruction of that ancient country, the bitter and brutal civil war, and the millions who seemed destined to spend the rest of their lives in refugee camps. There are things we as an international community could have done, and could do still, to help the people of Syria but the cost seems too high.

We could purge the oceans of plastic and halt global warming, if we wanted. But are we willing as a world to pay the price of changing our habits? We could tackle the housing crisis that is gripping our city and country. We could fix our NHS. We could ensure that our older people are properly cared for at the end of their lives, and that all young people receive a proper start in life. We could – on this Racial Justice Sunday – set aside all the instruments of racial oppression and mistrust. We could cure so many of our world’s and our society’s ills, IF we wanted. If we – and crucially those who hold the reins of power, money and authority in our world – wanted to and were willing to pay the price of the cure. And not just the monetary price but the price too of saying we were wrong, the price of national pride and honour, the price of changing our ways and our prejudices. Too often, though, like the rich young man, the cost of the cure seems worse than the disease, especially if you have to pay the price of the cure but others are suffering the consequences of the disease.

The challenge of these readings is not just about global challenges and domestic politics ‘out there’, though. The challenge is for ourselves as well. In our own lives, are we too afraid of being healed, at the cost it may involve? When I was in South Africa several years ago on a placement, I visited several townships near Durban with a local Methodist minister. Many of the people we met had been infected by AIDs and they spoke of how they had effectively been treated like lepers – shunned by their families and communities as unclean carriers of disease. I am delighted to report that it was the churches there who have been at the forefront of the attempts to bring relief and understanding. But those victims, and in fact all of the folk I met there, put my faith to shame. It was a living, visceral faith – a faith of an often desperate people, fully aware of their own shortcomings and their need for Christ. I am reminded of a verse from ‘Rock of Ages’, which we often sang there:

Nothing in my hand I bring,

simply to the cross I cling;

naked, come to thee for dress;

helpless, look to thee for grace;

foul, I to the fountain fly;

wash me, Saviour, or I die.

This is ‘old time religion’ indeed, and it, and the trusting faith I so often encountered in South Africa, seem a million miles from our modern, sophisticated lives here in Barnes. Yet, have we lost something vital as a result of our supposed sophistication? Have we forgotten to be honest to God, and honest with ourselves, about our own need for healing? Have we let ourselves be fooled into thinking that we are just fine as we are, with no need to change our habits and preconceptions in any way?

The challenge of these stories is not just to associate ourselves with Christ or Elisha. To say that we too would reach out our hand and touch the unclean – be they lepers or AIDs victims – important as that is. It is to recognise that we too need healing. We too need to recognise that we are desperate people, who need to be made whole again. We too need to be released from our pride and our fear, so that we may contemplate the radical healing which our world, our church and our communities need. We too are desperate for a cure that ultimately only Christ can give.

For it is in Christ alone that we are made whole. By him alone that our fears are destroyed. It is through his life, death and resurrection alone that we may make sense of an often senseless world. Let us be desperate for the cure, brothers and sister; not just for ourselves but for our world. And if we seek the cure honestly and fervently, then the cross of Christ assures us that he will do everything possible, and impossible, to give us and our world the healing we so desperately need. Amen.

Dear Pastor Farrar: What a marvelous message you delivered to Barnes M.C. this morning. Every Christian in America (Donna and I included) needs to hear a message like this. We live in a very non compassionate country here, more sexist and racist than perhaps any time in the last fifty years. We are so looking forward to coming to London those three weeks next September and attending church either in Putney or Barnes-or wherever you may be preaching. We will continue to look forward to how the Lord is using you in your position there. Blessings in Christ, Bob and Donna Johnson, Hendersonville, NC USA

LikeLike

Many thanks for the kind words!

LikeLike