This is the sermon I preached today at Putney Methodist Church. The text was Genesis 1:1-2:4, the first Creation story.

Introduction

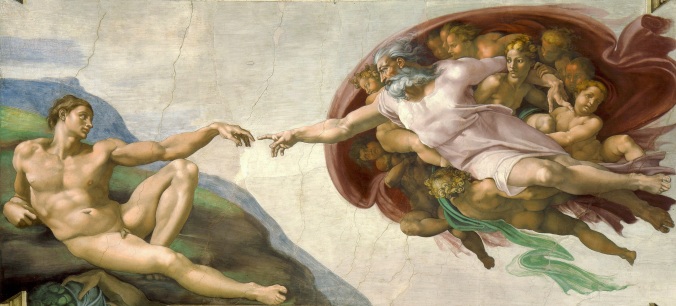

Creation of the Cosmos, from Monreale Cathedral, Sicily

In recent years, a new season has been added to the Christian calendar. At the initiative of the Orthodox Church, and others, we are being urged to consider the period from the beginning of September to early October as ‘Creation Time’. This is, of course, the period when churches have traditionally held their Harvest Festivals, as we shall do later this month, so the theme is one that is already in our minds. We will, therefore, be reflecting upon the theme of Creation in the coming weeks here at Putney, and there seemed no more appropriate place to start than with the first creation story itself.

The passage, of course, comes from the start of the book of Genesis, whose very title means ‘beginning’ in Greek (genesos). It is, at one at the same time, one of the most familiar and most controversial parts of scripture, and there has been a huge amount of debate about its interpretation over the centuries.

We do not have time to do justice to the full history of all the comment and debate that has raged over these verses this morning. All I would say now, is that we should note that this is the first of two creation accounts we find in the opening chapters of Genesis (1:1-2:3 and 2:4-3:24); we shall hear the second next week. In this first story, the writer describes God’s work of creation as a seven-stage drama, culminating with the day of rest. Many commentators believe this reflects the writer’s priestly origins, and his concern to demonstrate the importance of the sabbath as a sign of God’s covenant with Israel (Exodus 31:12-17). There is also an important emphasis on the orderliness of creation, and the separation of elements one from another (v. 4), which are also reminiscent of priestly concerns and functions.

Most importantly, though, I urge you to set aside all your preconceptions about this passage and listen to the beauty of its rhythm and cadence. It is easy to understand why it has captivated its hearers’ attention and inspired their imaginations for millennia.

Sermon

May the words of my mouth, and the meditations of all our hearts, be acceptable in your sight, O Lord, our strength and our redeemer. Amen

We will all hear and understand that wonderful passage from Genesis in slightly different ways. For some, it is a literal description of the creation of the world, in six 24-hour periods. For others, it is simply picture language, designed for a pre-literate, pre-scientific age. And there will be a million variations of understanding between those two poles. Too much time and energy has been wasted fighting over which interpretation is correct and I do not intend to waste any more this morning.

We will all hear and understand that wonderful passage from Genesis in slightly different ways. For some, it is a literal description of the creation of the world, in six 24-hour periods. For others, it is simply picture language, designed for a pre-literate, pre-scientific age. And there will be a million variations of understanding between those two poles. Too much time and energy has been wasted fighting over which interpretation is correct and I do not intend to waste any more this morning.

What most commentators would agree on, though, is that this passage came into its final form – the form in which we heard it read today, in translation from the Hebrew – after the period of the Babylonian Exile. That is, very roughly, 300 to 500 years before the time of Christ. A lot of the material, we know for certain, is much, much older than that but it was shaped and edited together after the experience of defeat and humiliation at the hands of the Babylonians. This is important because, as we know, Genesis was clearly influenced by many Near Eastern stories and myths, perhaps most famously the stories around Noah and the Flood. But the people who told and re-told these verses did not just slavishly copy such legends; they subverted them. Inspired by the Spirit, we believe, they reshaped their material to make important theological assertions about the God whom they knew and worshipped. They told stories that spoke God’s truth into their contemporary world, often in defiance of its dogmas and doctrines.

The challenge for us today is to find God’s truth within this passage for our own times. Rather predictably, I am afraid, I would highlight three important abiding truths today.

The first is that we are created beings: “In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth” (Gen. 1:1). The passage tells us that our creation was a spontaneous and unprovoked action by a God who revelled in the very act of creating. The purpose of creation, was the creation itself!

The creation of the world from the Nuremberg Chronicles.

Like much else in our story, this contradicted a lot of the stories that the ancient Israelites would have been exposed to in their contemporary world, especially when in Babylon. We do not have time to explore many of these fascinating legends in detail, but in them creation often seems to have happened by accident or by coincidence – because one god or goddess did something, and the world just happened to come into being. Often, creation was the by-produce of some sort of cosmic fight or struggle. It is almost as if we said that the purpose of digging in your garden was to produce the sweat on your brow, or that the purpose of baking a cake is to create a lot of bowls and utensils that need to be washed up!

The ancient Israelites, though, were inspired to tell a story that spoke of a God who willed Creation into being. There is no ulterior motive, no convoluted chain of accidents: God spoke Creation into being because God wished so to do. That was a radical statement in the ancient world, because it gave value and purpose to all creation, especially the culmination of that creation: humanity. It stated that people and the world around them were not simply an unwanted side-effect of cosmic battles or the play-thing of the gods, but were the Creator’s purpose and joy.

That remains a radical statement today, because it means that all creation and lives have meaning and purpose. It does not promise that we shall fully understand that purpose and meaning in this life, but it suggests that we were all created by God’s clear intention. We are not simply a cosmic accident that took place because the right set of chemical molecules happened to be in the right combination at the right moment – even if that is how the physical process of making a human occurred.

When we gaze up at the night sky – if we can see it clearly in London ever! – at the “lights in the dome of the sky” (Gen. 1:14), it can make us feel terribly small and unimportant. Yet as we discover more and more about our universe, we realise how incredible is the very fact of creation, how miraculous it is that we live on a planet capable of sustaining life at all, when we now know how many countless millions of planets out there cannot. Instead of feeling small, it should make us feel special, privileged and important. This story tells us that you and I were meant to be here; we were knowingly created and lovingly made. That was ‘good news’ three millennia ago, and it remains so today. More people need to know that their lives are not a failure, not waste but are a precious gift from a creator who loves them.

When we gaze up at the night sky – if we can see it clearly in London ever! – at the “lights in the dome of the sky” (Gen. 1:14), it can make us feel terribly small and unimportant. Yet as we discover more and more about our universe, we realise how incredible is the very fact of creation, how miraculous it is that we live on a planet capable of sustaining life at all, when we now know how many countless millions of planets out there cannot. Instead of feeling small, it should make us feel special, privileged and important. This story tells us that you and I were meant to be here; we were knowingly created and lovingly made. That was ‘good news’ three millennia ago, and it remains so today. More people need to know that their lives are not a failure, not waste but are a precious gift from a creator who loves them.

The second reflection I would make this morning is that the Genesis story tells us, incredibly, that we are made in the very image of God. “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness” (Gen. 1:26). What exactly this means is intriguing. When we look around even this small congregation here it gives us a great variety of potential images of God! The most likely interpretation is that we share the ability to think, create, destroy and choose good or evil with God.

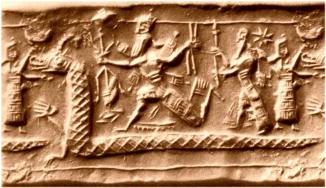

Depiction of Babylonian creation story from the Enuma Elis.

Once again, though, this is a radical departure from much of what the ancient Israelites’ contemporaries thought they knew. Not only was humanity often merely a by-product of creation, in many ancient creation myths, but humans themselves were meant to know their lowly place. In one Babylonian myth, humans were created effectively as a slave race for the gods and goddesses, who did not wish to work for themselves. They were meant to till the soil and raise animals, solely in order to make offerings to the deities, who lived like parasites off their labours. They were very clearly at the bottom of life’s heap!

Here, though, humanity is the crown of God’s creation – and God bestows on us the ultimate privilege of bearing the imago dei, the image of God. This means that – incomprehensibly – within each one of us, there lurks a spark of the divine – there is something of God in each and every person on the face of the planet that has ever lived and will ever live. This gives an enormous value to every human being and was a revolutionary contradiction of so much contemporary thought and belief when these words were first set down by that priestly writer so long ago. It does not say that ‘some’ people were made in the image of God – men, Israelites, an elect – but all

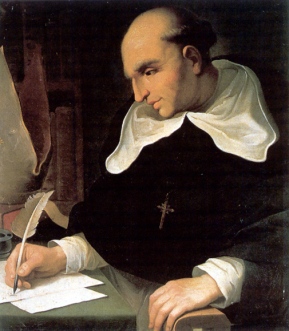

Bartolomé de las Casas

For the Israelites, labouring in slavery in Babylon, being told by their captors that they were a defeated, worthless people, this was a powerful message of hope, and it has continued so to be ever since. The ‘discovery’ of the Americas after 1492 by Europeans prompted a huge debate about how the newly-discovered peoples should be treated. As non-white and non-Christian ‘aliens’, many conquistadors believed that these people had no inherent rights or value whatsoever, and regarded them all as merely potential property to be exploited. Christians like Bartolomé de las Casas, though, pointed to verses like those we have just read to argue that all humans have inherent value in God’s eye, for God chose to make them all in God’s own image.

It is from such Christian texts and thinkers that the modern concept of human rights developed, and so many great battles fought and won, not least the battle against slavery. And the radical nature of that statement in the very beginning of our scriptures remains as powerful now as it was three millennia ago. That our value is not based on appearance, or wealth, or status, or nationality, or ethnicity, or anything else which our material world prizes so highly. It is based solely on the simple fact that we are all somehow made in the image of God, our Creator and Sustainer.

The third, and final, point I would make this morning is that our passage very clearly tells us that Creation is good. This is the constant refrain in our passage today, repeated at the end of each day: “And God saw that it was good.”. Christianity has had something of a complicated relationship with the material world, often seeming to devalue it at the expense of the spiritual and the ethereal. Yet in this passage we see a bold assertion that all of the created world – birds, trees, insects, fish, stars, planets – is somehow blessed and inherently good. It is a clear hint that perhaps even in the material world, we can catch a glimpse of the divine; we see something of God – God’s nature and God’s desires for us.

I was reminded of this over the summer, when I was walking in the Lake District, a place where it is very easy to fell close to our Maker. We came across the most beautiful flower and I was told that it was a Common Spotted Orchid. It is incredibly beautiful and did not seem very ‘common to me’. A few weeks later, I was at Kew Gardens and happened to read an information panel about orchids in one of the greenhouses. From it I learned that there are over 28,000 kinds of orchids in the world, and each year they discover many more. (The Aster family has a similar number.) Why do we need so many kinds of orchid in the world? The short answer is, ‘we don’t’! Instead, this simple flower reflects the over-flowing abundance of God’s love for his Creation and his desire for it to be as wondrous and beautiful as possible.

I was reminded of this over the summer, when I was walking in the Lake District, a place where it is very easy to fell close to our Maker. We came across the most beautiful flower and I was told that it was a Common Spotted Orchid. It is incredibly beautiful and did not seem very ‘common to me’. A few weeks later, I was at Kew Gardens and happened to read an information panel about orchids in one of the greenhouses. From it I learned that there are over 28,000 kinds of orchids in the world, and each year they discover many more. (The Aster family has a similar number.) Why do we need so many kinds of orchid in the world? The short answer is, ‘we don’t’! Instead, this simple flower reflects the over-flowing abundance of God’s love for his Creation and his desire for it to be as wondrous and beautiful as possible.

I am sure we have all had similar experiences at sites of natural wonder, or when seeing programmes like Blue Planet. Moments when we come face to face with the sheer beauty, variety and wonder of Creation. (We shall think more about what it means to be good stewards of that Creation in the coming weeks.) Our reading this morning, though, seems to tell us that such encounters give us a glimpse of the divine nature of God. And they remind us that we, like Creation, were made for good. We were made to reflect the glory and wonder of God, and of his limitless love for his creation. We were not all made to be the same but, like the orchid, to reflect the boundless diversity at the heart of God. And we are all an integral part of that good Creation: designed to reflect the glory of our Creator.

In a few moments we shall celebrate our holy communion. In that celebration, we shall link the very beginning of our Creation story with its ultimate fulfilment. In celebrating God’s incarnation in the person of Jesus Christ, we are remembering how God did not despise his Creation and simply wind it up at the beginning of time like a clockwork toy and let it play out its inevitable course, unaided and alone. We are remembering how God chose to love and bless his Creation with every good thing, and how he remained intimately involved with its evolution and history. We recall how he chose to become a created thing, made – like us – in God’s own image, blessing and sanctifying each one of us. As we celebrate all that God has done for us in Christ, we use the fruits of creation – bread and wine – to recall our unique place in God’s story, our inherent value as created beings and the greatness of God’s love for each one of us. “God saw everything that he had made, and indeed, it was very good.” (Gen. 1:31) Amen.